The objectives of sustainable development are to meet the economic, social, and environmental needs of the present, without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Supporting strong healthy communities involves fostering well designed, safe environments with the spaces, places and facilities that support communities’ health, social and cultural well-being. Enhancing and protecting our natural, built, and historic environment requires effective use of resources, adapting to climate change and moving to a low carbon economy. [1]

In June 2019, the UK legislated a net-zero target for carbon emissions by 2050. In April 2021, the Government enshrined its commitment to cut carbon emissions by 78% by 2035. These moves have a lot of public support. Meeting these targets is a huge challenge though. Innovation and new technologies will play their part but fundamental changes in our society and economy are also required. Hitting the legislated targets will only be achieved if Government, regional agencies, and local authorities work together successfully.

More than half of the emissions cuts needed rely on people and businesses taking up low-carbon solutions. These are decisions that are made at a local and individual level. Many of these decisions depend on having supporting infrastructure and systems in place. Local authorities have powers or influence over roughly a third of emissions in their local areas [2]. We’ve got to change our habits and expectations about what it’s ‘ok’ to do, but the onus is on the Government and local authorities to develop the strategic frameworks and policies that will support the delivery of Net Zero.

The built environment, with the construction sector, is the third highest carbon emitting sector in the UK, contributing up to 40% of the country’s carbon footprint [3]. Local authorities manage the built environment through the planning system, according to national and local policies. Over 300 local authorities have declared climate emergencies, and a third have developed strategies and action plans to deliver ambitious targets by 2030 and 2050.[4] How does this commitment materialise in approaches to the built environment? Are we on track? Is there more that could be done? The Council for British Archaeology (CBA) believe there is an ‘easy win’ to be had, that minimises unnecessary carbon emissions whilst also maintaining a sense of place.

This is where we are coming from. The CBA have a statutory role within the planning system as a consultee on proposed changes to the historic environment, specifically listed buildings, but encompassing broader aspects of places. We provide advice, through our casework, on where proposals may cause harmful impacts on the significance and special interest of a place. Change, renewal, and the evolution of a place is an inherent part of its identity through time. Understanding which parts of a place hold significant traces from the past helps inform appropriate change, that retains what people value whilst enabling contemporary wants and needs to be met.

Listed buildings are protected within the planning system, but not everything that people value about their place is designated. Lots of local planning authorities maintain a ‘local list’ of places that matter to local people, but don’t meet the criteria for statutory designation. However, when push comes to shove in the planning system, being locally listed often offers little or no protection from demolition when an old building is in the way of a new development scheme.

Unless there are clear and convincing reasons to support the demolition of locally listed buildings, which offer sufficient public benefits to mitigate the harmful impacts of losing the structure, the CBA is against the demolition of locally listed buildings. From a historic environment perspective, they often contribute to the character of a place and represent what makes somewhere unique. From an environmental perspective they contain tonnes of embodied carbon.

The Climate Change Committee (CCC) assesses the UK’s progress in reducing emissions and adapting to climate change. The key message of its 2021 Progress Report to Parliament(link is external) is that despite the government’s historic climate promises in the past year (for which it deserves credit), it has been too slow to follow these with delivery. The CCC has found that “this defining year for the UK’s climate credentials has been marred by uncertainty and delay to a host of new climate strategies. Those that have emerged have too often missed the mark. With every month of inaction, it is harder for the UK to get on track.” A recommendation from The CCC’s progress report is establishing a Net Zero Test to ensure that all Government policy, including planning decisions, is compatible with UK climate targets.

The CBA are not aware of a single local authority who have made the leap from the ‘presumption in favour of sustainable development’ to ‘a presumption in favour of the adaptive reuse of locally listed buildings.’ Why not? The prioritisation of refurbishment over demolition is inherently sustainable, as the waste of many materials with carbon already embedded in them would be avoided.

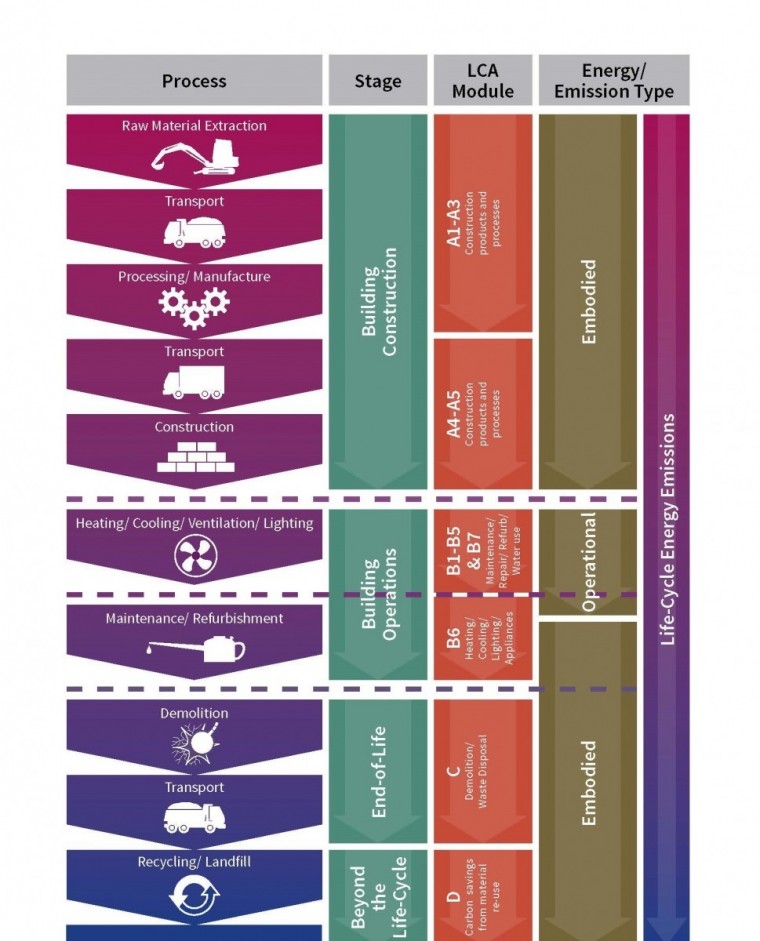

Local authorities have the powers to ensure that buildings meet basic energy efficiency standards. This is broadly enforced across new build developments, where requirements about materials and thermal efficiency ensure that buildings have minimal daily emissions from heating and power usage. Old buildings are widely viewed as inefficient in terms of energy usage, based on their ‘leaky’ construction.[5] Arguments around the sustainability credentials of new buildings are often presented in support of demolishing standing structures.

However, the mindset that old buildings are inefficient in terms of energy usage focuses solely on their daily emissions, overlooking the carbon embodied within the building and the carbon lost through demolition. Old buildings already embody significant CO₂ in their materials. The fact they have been standing for tens to hundreds of years supports the truism ‘The greenest building is one that’s already built’. The adaptive reuse of standing buildings is inherently sustainable. New buildings are a major source of resource use and waste production. It follows that a key tenet of a sustainable built environment is effectively extending the useful life of existing buildings by improving them. There are also many ways to reduce the daily emissions in historic building stock through retrofitting.

Compelling research into the embodied carbon in pre-1919 building stock(link is external), commissioned by Historic England, demonstrates the imperative of not wasting the embodied carbon in standing buildings if the UK is to reach its legally binding commitment to be carbon neutral by 2050. This research has shown that reuse through refurbishment and retrofit, rather than demolition, has the potential to reduce carbon emissions by more than 60% by 2050.[6] On this basis why not make the logical move from a ‘presumption in favour of sustainable development’ to a ‘presumption in favour of adaptively reusing locally listed structures.’

When there is a degree of contention about demolishing a structure to construct a new build, versus adaptively reusing the standing building, an ‘options appraisal’ is often required by the local planning authority. This generally includes a viability assessment by the developer, which boils down to cost. This is where the crux of the problem lies for developers, and where the government could really help solve the problem.

Work to historic buildings is subject to 20% VAT, yet no VAT at all is charged on demolition or new build. HMRC regulations state that for a development to qualify for no VAT “any pre-existing building must have been demolished completely, all the way down to ground level.”[7] This incentivises the demolition of old buildings rather than repairing, maintaining, or altering them. Incentivising reuse and repair through an equalisation of VAT would create more of a level playing field, rather than incentivising demolition.

In 2020, covid 19 lockdown measures led to a decrease in UK emissions by an impressive 13% on the previous year. Obviously, this was made possible by the country grinding to a halt for months whilst we all stayed at home. Sustaining 2020s reductions in carbon emissions, whilst supporting a ‘covid recovery’ to every aspect of our lives, will require sustained Government leadership, underpinned by a strong Net Zero Strategy. These are The CBA’s suggestions towards achieving this.

-

Establish a presumption in favour of the adaptive reuse of standing buildings, especially locally listed structures. Demolishing standing structures and re-building is inherently unsustainable in terms of carbon emissions. Other benefits from maintaining existing buildings for the historic environment should also be recognised. Many buildings represent more than just a set of walls and a roof, they embody local character, represent local people and are inherently integrated into the sense of place of a local community. There are social, health & wellbeing, cultural and economic benefits to an area that are strengthened by to its locally listed structures and their contribution to the character of the built environment.

-

Create parity in the VAT rating for the repair and maintenance of standing buildings, when compared to demolition and rebuild options. This would improve the financial viability of repair and maintenance of existing buildings for the construction sector as well as being more environmentally sustainable.

We would love to hear your views on this topic. Please get in touch.

[1] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1005759/NPPF_July_2021.pdf#page=1&zoom=auto,-274,843

[2] Findings of The Climate Change Committee, Local Authorities and the Sixth Carbon Budget, 2020.

[3] https://historicengland.org.uk/content/heritage-counts/pub/2019/hc2019-re-use-recycle-to-reduce-carbon/

[4] https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Local-Authorities-and-the-Sixth-Carbon-Budget.pdf

[5] A majority of pre-1914 structures have drafts, which are an inherent part of their design and construction. Air bricks under suspended wooden floors prevent rot and infestation. C18th and C19th buildings have high ceilings and large areas of single glazed windows – amazing for natural light, poor on thermal efficiency.

[6] historicengland.org.uk/content/docs/research/understanding-carbon-in-historic-environment/

[7] https://www.gov.uk/guidance/construction-services-and-zero-rated-relief-vat-information-sheet-0717