My name is Lauren Nofi, and I guess you could say I’m an early career archaeologist though I’ve been working for almost a decade. It’s complicated. Every terrible job, and every wonderful job, I have had since graduating has been a means to an end: the goal of moving back to the UK from the US permanently to work in archaeology.

I jumped right into a masters at the beloved-but-now-closing Department of Archaeology at the University of Sheffield as soon as I graduated with my BA. I learned so much in the classroom and in the field over that year, and I knew the UK heritage sector was where I was supposed to be. One hitch: our large cohort of international students submitted our dissertations and immediately our student visas expired.

We were suddenly not wanted in the system where we had been developing professionally, networking and collaborating for a whole year. There had been a provision for international students to work after a UK postgrad program, but that was cancelled in 2010. Even with that option off the table, the gameplan for my future had seemed so simple: get a work visa and live happily ever after. Naïve. At the time, a grand total of two archaeological companies sponsored visas. In the years since, the shortage occupation list has included archaeologists but the minimum salary was far beyond any entry-level archaeologist’s dreams to qualify for sponsorship.

I moved home and scoured the American job market endlessly. The heritage sector in the US is nothing like that of the UK: you either work for a university or a commercial (Cultural Resource Management) firm, as community archaeology is virtually non-existent. Unless I pursued a PhD or a commercial job, I would only be skill-building a few weeks a year, entirely by using vacation days from a non-archaeology job to go on the few digs open to non-students. That’s not sustainable. I know, because I tried.

Thinking back to what felt like an endless cycle of non-archaeology jobs, only to save up for summer volunteering in the UK, I understand how privileged I was to even attempt it. 0 out of 10, would not recommend that for anyone. Professional development that should have taken a year took several. My burgeoning expertise in British archaeology from all those volunteering stints was seen as completely useless in the US, even though the fundamentals of excavation are pretty standard. On the other hand, community digs and non-profits in the UK scrambled to make room for me on their summer teams, valuing my experience more than even I had been. I finally thought I saw a way out of the cycle: prove my Italian citizenship, get an EU passport, and migrate. More on that later.

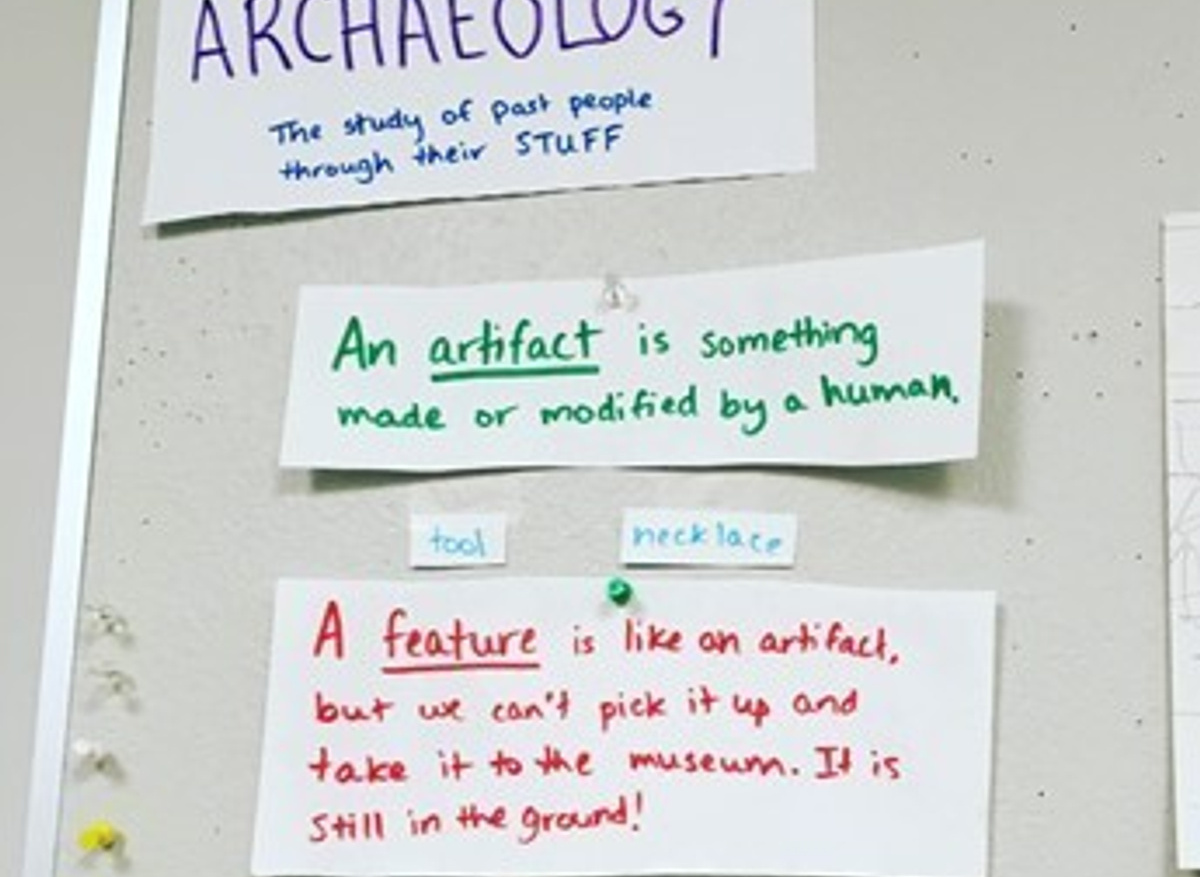

The cycle did eventually include archaeology and archaeology-adjacent jobs here in the US. I spent some time in a recent grads’ program at a Smithsonian museum where I learned collections and curatorial skills. I sucked up my disdain for shovel-test pits, the hallmark of American CRM, miserably digging small holes in the forest on a twentieth-century army base (with unexploded ordnance!)—nothing like what my friends in commercial archaeology in the UK were doing. Everything felt hit-or-miss for several years. But then a painfully-short dream job contract at a living history museum changed my professional trajectory: archaeological education and outreach was what truly moved me. But where in the US could I do this?

In 2018, the natural history museum in Pittsburgh (the Sheffield of America) sent out a call for educators, which seemed like the perfect opportunity. I started working year-round, delivering programs on- and off-site, for both students and elders, on subjects like archaeology, Egyptology, geology, palaeontology, etc. I have my own classroom for home-schooled students during the school year and teach courses in the summers. The museum has been my home for several years now, making me a better teacher and communicator with every new assignment.

Finally settled into a routine, of course that was when my citizenship came through. I picked up another job to save for the impending move. I began applying for jobs throughout the UK, securing offers predicated on the arrival of my Italian passport (another lengthy pursuit) that proved my right to work. I received my passport two weeks before the Brexit settlement eligibility rules changed. I had two weeks to pack my entire world up and move across an ocean (again). There was no way I could pull this off. I’m the master of questionable moves for jobs, but even this was too much for me. Was I more mature now? Maybe. But also more precarious, with the pandemic and resulting furloughs from both jobs leaving no safety net of savings.

So I stayed. That was my last chance, unless some big change to migration policy opens the window again. Several organizations I had applied to are now on the sponsor list, which would have been helpful for me a year ago, but I will stifle my bitterness with the optimism it represents for myself and other international archaeologists trying to migrate.

Making peace with the current situation was hard. I was angry for a long time, but I have started opening up (or kicking down) doors to new opportunities; I know how to advocate for myself as an expert now. As museum projects move forward, I’ve been tapped as a lesson plan consultant and committee member for a game-changing redisplay of a major exhibit. I’ve also formed relationships with local eighteenth-century archaeological sites that have booked me as a freelance consultant and educator for archaeological and history programs. While this is not exactly what I expected to be doing eight years on from my masters, I know I’m working towards something bigger.

I’m not sure there’s a moral to this story, because it’s still being written. I guess the best I can say is to take the opportunities that move you, that really make you proud to be an archaeologist, when you can. Those experiences will make a difficult journey easier.