As a researcher who looks at torcs, the pandemic of 2020/2021 has been a strange time. Unable to visit the torcs that are the basis of so much of our work, myself and my torc-partner-in-crime, Roll Williamson have been forced into a virtual world of catalogues, online images and whatever can be achieved at home.

At this time last year things looked bleak but, looking back, we have achieved much. As with many archaeologists, most of what we do moved online: Zoom became the means of connecting with conferences and collaborators. We gave talks and met with people from across the country, and the world, in ways we might not have done before Covid. We published an Open Access, peer reviewed, paper on our website, The Big Book of Torcs, and created several blogs.

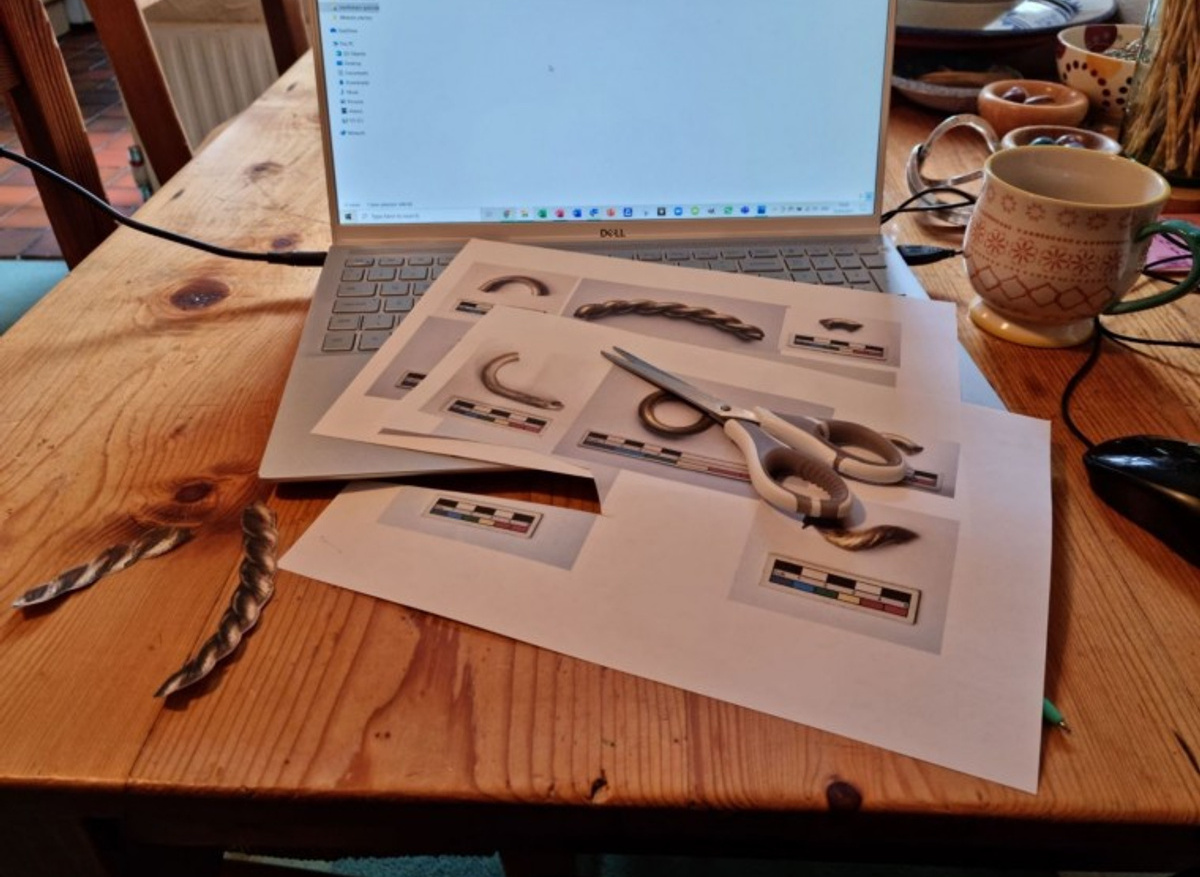

We also spent a lot of time online, scanning through museum catalogues. Looking through the torc finds from Snettisham, several very distinctive pieces of torc caught my eye. Having a very specific manufacturing method, and being heftier than most torcs, it was easy to collate all the photos of the unique torc pieces. But was it one torc, a part of a torc, or perhaps even more than one torc, made in the same way? Stuck at home with no access to the actual pieces, there was only one way to find out: scale all the photos of the pieces to the same size, print them out, cut them up and see what fitted where and, sure enough, once the torc jigsaw was finished it was obvious: a single complete torc with only one part of the double ring terminal missing.

In another moment of lockdown rashness we also purchased a piece of gold. A 10g Smartie sized piece of fine gold loveliness...and an anvil, a blow torch, some fire bricks and a hammer...and then dapping blocks, a few more hammers and a couple of punches...and a big piece of wood to mount the anvil on. This gold working business is addictive!

We melted gold, we hammered gold, we made wire, we made sheet and, as we discovered, if you want a good way of relieving stress, zapping a piece of gold into a tiny glowing puddle with a blowtorch is a very good way to do it! We even taught my daughter Nell's best friend, Amelia, how to do it too. In the process we learnt a lot about gold, how it behaves and how best to work it.

Meanwhile, the catalogue delve, as well as providing many new insights, also threw up a few oddities, the strangest of these being at least two pieces of torc from Snettisham which appear to have been - and there is no other way of saying this - chewed. Yup, that's right: two pieces of gold that appear to have been actually properly bitten. Leaving tooth marks.

Now of course any archaeologist worth their salt would need to be able to prove that these were indeed tooth marks, so what to do? Luckily, we just happened to have a freshly hammered piece of sheet gold that we could use. But first we needed to practice and what better material to practice with than cheese!

Having proved our methodology, it was time to get the gnashers into £500 worth of gold........and it worked! We managed to replicate the tooth marks from both Snettisham pieces. Now, of course we will need to see the two Snettisham gold pieces to properly establish whether these are indeed bitten, but at present there is nothing to rule out that there were, for whatever reason, 'Torc Tasters' at Snettisham (Oh, the Iron Age really is truly bonkers sometimes!)

So yes, by today, this Day of Archaeology 2021, we have rifled catalogues, written a paper, made a torc jigsaw puzzle, torched gold and chomped cheese. But can we please get back to looking at torcs now before we do something really ludicrous? ;-)