Letter To A Young Archaeologist December 2023

This is our final Letters to a Young Archaeologist instalment, closing two years of contributions from across the sector, from established and early career historic environment professionals. We have had a huge variety of 'letters' in all sorts of media, from the traditional letter to online gaming, video and pieces of art.

To celebrate the series, the Council for British Archaeology asked members of its newly formed Youth Advisory Group to reflect on the collection of letters. What are its strongest themes, what are the big takeaways and how do we act on these? As you will see, our Youth Advisors have lots of reflections and ideas for the future.

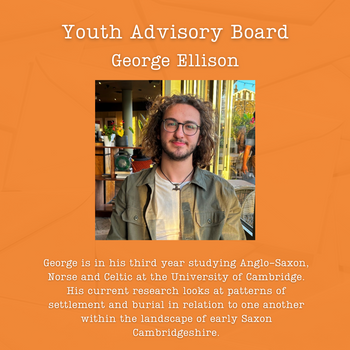

George Ellison

Hi, everyone. I'm George and I'm one of the Council for British Archaeology’s Young Advisors. Reflecting on the last two years of the ‘Letters to a Young Archaeologist’ series, there was one thing that amongst all of the great advice and all of the encouragement stood out to me as being common between all of the letters. And that was an acknowledgment of the importance of us as the future of archeology and the hope that that seems to bring.

There is real belief that we, as young archaeologists, have the power to bring about positive and lasting change to archaeology, to the climate crisis, to political narratives and to social beliefs, and that we have a lot to offer through our hard work, our imagination and our ideas, and perhaps most importantly, through our passion.

It's important that we take every opportunity that we can to engage in archaeology and that we make the most of those opportunities to inspire positive change. It's important that we form our own opinions, but perhaps more important that we listen to those of the people around us, especially those who face barriers that we might not know or understand. And in that light, it's important that we make opportunities as much as possible for other people.

We should all have a hand in reshaping the future of archaeology and re-imagining what it means to be an archaeologist. We need to think not just of those who dig or those who get paid to do archaeology, but also of those who occasionally join digs or those who like to watch documentaries or read books about archaeology. We need to think of all of the people involved in archaeology and the value that they bring. Without any one of these people, archaeology and heritage will suffer.

And those of us who do wish to make archaeology a career, we need to fight this from the inside. We need to reimagine the industry and push it in the right direction every chance that we get. We need to fight outdated views about who can or should be an archaeologist. We need to break down barriers that have prevented so many from accessing archaeology, and we need to take every chance to listen to those around us so that we never forget what is so important, which is that to protect archaeology, we must first protect archaeologists.

And finally, to everyone, we are the future of archaeology. We have the power and the potential to bring about positive change to archaeologists, to archaeology, to climate change, to the future of humankind. We must take every opportunity that we have to engage and inspire with archaeology. We are the future of archaeology, we are all archaeologists, and the time to act is now.

Eva Murray

Where is community archaeology, and what is it?

As a final-year archaeology student who is in the midst of planning for post-grad life, ‘Letters to a Young Archaeologist’ is a project that is pretty relevant to me. From the environmental work of Dr Ben Gearey, to the many different paths taken from the team within the European Society of Black and Allied Archaeologists, these letters displayed a wide spectrum of paths and opportunities that are out there within the archaeology profession. A particular aspect I was interested in was the role of community archaeology, and what different ways of helping, supporting, and involving community are present within archaeology today, and I wanted to see what the letters could teach me about this.

In the beginning of my interest in community archaeology, I understood it as something that was done mainly in reference to working on excavations, and this came in the form of teaching the local community around the site about the work that is being done and supporting the running of community dig days. In addition to this, archaeology in the form of museum education, was also an option to get people of all ages interested in archaeology. These are both very important; however, the letters supported an expansion of this definition.

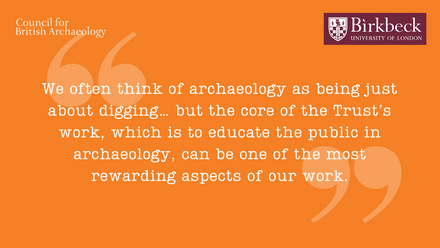

The letters demonstrated to me a growing presence of community archaeology across the archaeology profession. The importance of the application of community involvement is shown in various forms, such as Hannah Barrett discussing the huge impact that having a more community-focused project can have on commercial digs, and how it is key in producing high quality and diverse results from sites. In terms of interpretation, the role of involving wider communities is vital for accurately interpreting the complexity of past society, as discussed by Audrey Horning. Together with the work of groups such as the Young Archaeologists’ Club and work within archaeology trusts such as English Heritage and the National Trust, the opportunity for supporting and working within community archaeology projects was highlighted as a job that is present, and important.

‘Letter to a Young Archaeologist’ has demonstrated this current presence of community archaeology within the profession, where opportunities are, and how accessible the said opportunities are. The letters from groups such as Enabled Archaeology and Zeynep Kuyssa address limitations and spaces of hesitation that many people have, such as the questions of inclusivity, accessibility, diversity, general pay issues and more. Together, the letters show that there is opportunity and a necessity for ideas of change, passion, and voice to be heard across all aspects of archaeology. By working together, these ideas can bring about even more new and different paths, creating an even more accessible future of archaeology for everyone who wants to be involved. The letters are an exciting opportunity for having conversations, as seen in the inclusion of youth response letters in 2023, around change, while also supporting a wider picture of varying opportunities and paths in archaeology.

Future developments of the ‘Letters to a Young Archaeologist Project’ can be the generation of some actionable points from these conversations, ones that will help more and more people become involved in archaeology and heritage. Through the continuation of the clarification of the wide range of opportunities and paths into the profession, while also the continuation of working with young (and old!) people to give and create space or new ideas for directions, this will hopefully continue to generate exciting new ideas and projects between new and old archaeologists of all levels.

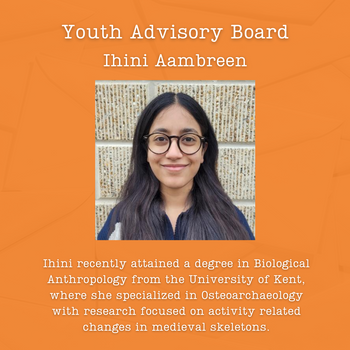

Ihini Aambreen

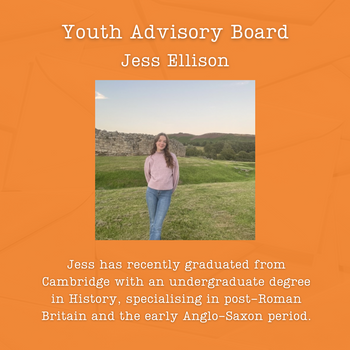

Jess Ellison

Dear Young Archaeologists,

The 2023 series of Letters to a Young Archaeologist have highlighted a number of organisations within the archaeological sector, and illustrated the extent to which a supportive network of peers as well as professionals is available to an up-and-coming young archaeologist. We have heard from organisations such as the Enabled Archaeology Foundation, as well as voices from the ‘Reclaiming African History’ project, both of which champion and support marginalised groups to participate further in archaeology. We also heard from members of the Youth Engagement Team at English Heritage, as well as two of the National Trust’s longest serving archaeologists, who illuminated further what it is like to work within the sector. All together, these letters form a fantastic resource for the Young Archaeologist; they demystify and reveal what it is to be further involved in archaeology, and for this they are invaluable.

What is more important perhaps, and what should be the principal step for any budding archaeologist beginning their journey, is realising and believing that it is all achievable for you. At least for me, hearing from a range of professional figures within archaeology, in positions I would love to one day have, or in organisations I would be delighted to be a part of, can be intimidating. As the Letters have shown, there are a massive variety of opportunities and organisations out there, and although this is exciting and almost comforting, it can be overwhelming when deciding what steps you should take next. When overwhelmed, it can be hard to realise that what you think of as aspirational is actually realistic and achievable, but it will not be if you don’t first believe in yourself and overcome any self-doubt. Everyone who has participated in the Letters to a Young Archaeologist was in your position once, and it is entirely within the realm of possibility that you will one day be in their position too.

There is no reason that it cannot be you who succeeds, and overcoming any sort of impostor syndrome will be your biggest obstacle. The Letters to a Young Archaeologist have illustrated the friendly figures and organisations that are out there, so build your confidence, your network and your understanding of the sector further by taking the first plunge and get involved. Join a community dig in your area, volunteer at a local site of historic interest, take part in any number of the youth engagement schemes out there, make your own opportunities, and realise that you can do it too.

George Knight

To finalise the series, George has contributed a letter which shares his knowledge and experience of working within heritage and archaeological consultancy. In doing so, he aims to summarise the many varied past and present experiences and themes of working in heritage shared by previous contributors and to look towards the bright future, where future archaeologists, in their many different forms, will thrive.

In keeping with the letters previously published,

Dear Young Archaeologists,

The world is changing, and archaeology with it.

Over the last half century, archaeology has embedded itself in the public consciousness as an exciting endeavor that unearths lost artefacts and tells us more about our collective past. What is often missed however, is that most of these miraculous survivals were not just chance finds, but were recovered through the diligent work of thousands of professional archaeologists, who individual careers have built a multi-million-pound heritage industry which only a generation ago barely existed. The earliest philanthropic days of ‘rescue archaeology’ during the 1960s-80s, when groups of rag-tag enthusiasts appeared on constructions sites with trowels in hand has now evolved into a full environmental discipline, with heritage specialists involved in every stage of major development schemes like HS2 and London’s Cross Rail.

It is within this latter bracket that heritage consultants like myself reside. We work as advisors between the client (the business paying for a scheme) and the contractor (archaeologists or conservators working on site), to provide the appropriate advice and strategies for dealing with any heritage assets affected by their schemes. Our work usually compromises producing assessments of impact, monitoring the delivery of fieldwork and, occasionally on large projects, being fully embedded within the clients team as an ‘Archaeological Clerk of Works’ (or ‘ACoW’), who is responsible for providing day-to-day supervision and advice to ensure the scope of works and heritage are equally respected.

As significant as our role seems now, it only became so due to the mandatory heritage protection laws PPG 15 & 16 which, 30 years ago, placed responsibilities to protect both buried and built heritage on developers. Before this, only specific heritage assets received government protection through designations like listing or scheduling, and most were only administered to by small heritage organisations when affected by development. Post-PPG was really when the age of career archaeology really began, as the historic environment was legislated to be of universal concern and became commercialised. This led to a new wave of full-time archaeologists conducting developed-funded excavation, and from the requirements of these projects spawned the consultant, or ‘planning archaeologist’, who liaised directly with the client on what they mitigations they needed under these new laws. Since that time, as the roles become defined in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) of 2012 and Construction (Design and Management) Regulations of 2015, our position has strengthened and grown, but I have no doubt that our roles will again transform as new governments, technology and climate change transform our world.

While this uncertainty can induce anxiety, I think the unknown provides an opportunity for hope. If the last three decades of archaeology can be taken as an example, then it seems likely that there will be new and diverse careers yet to come. Just as there became a need for full-time archaeologists, and it may yet be that future circumstances and technologies will generate new roles we cannot even imagine. Society has already demonstrated that it increasingly appreciates heritage and will hopefully support your careers just much as it has ours.

My recommendation for young archaeologists is not just look to the past, but to explore the future and appreciate that their careers may be far more varied than they anticipate. To make yourself ready, learn broadly, study with an interdisciplinary approach and engage with the world in which you work, as this will dictate your path just as much as our expertise and experience will.

I wish you the best of luck.

Yours faithfully,

George