Letter to a Young Archaeologist, October 2022

Dear Young Archaeologist,

Welcome to the fold! If you are reading this, you have probably already had to come up with a compelling answer to that perennial question, what’s the point of archaeology? And if you haven’t already been asked that question, trust me, it will happen. I have so many answers to that question, all of which are rooted in the present day. Like it or not, the past matters and it’s always with us, shaping our lives, constraining our lives, yet also enabling our futures.

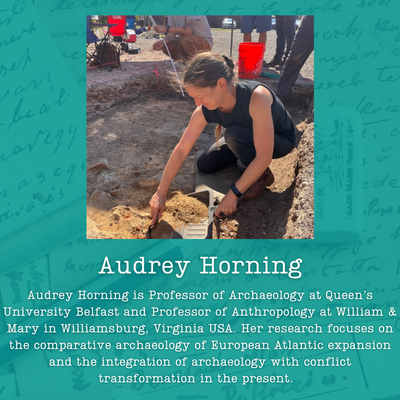

So why do you want to be an archaeologist? The South African archaeologist Carmel Schrire once wrote that she became an archaeologist so she could ‘drive around in a big Land Rover, smoking, cursing, and finding treasure.’ I can’t say my own motivations were quite the same, but probably not far off. Fun and adventure were certainly part of the allure. While I still love the physicality and comradery of fieldwork and the thrill of a discovery, I have come to appreciate that for much of its history archaeology has been a very exclusive practice that has done inadvertent and sometime intentional harm. Archaeology was born out of Western colonial expansion; digging up someone else’s past as another means of taking without permission. We must own that history and turn it around. To do that, we must stop making archaeology all about us, the lucky archaeologists in our boots and hats and Land Rovers (ok, in my case a clapped-out Proton), and recognise the validity of multiple claims to the past.

My archaeological practice focuses upon exploring early modern colonialism and its ongoing impacts. Such work is invariably and even de facto political in nature, whether I am working across the sectarian divide in Northern Ireland or working for African American and Native communities in the US. For me, this is inspiring, my way of being an active and involved citizen. The contested nature of the recent past lends a real power and currency to the archaeological record because it always contradicts tired old traditional narratives- which means that when communities take charge of its exploration, archaeology can be genuinely transformative. Through my work in such settings I have learned the value of facilitating rather than directing; of listening rather than lecturing. What do people want to know, and what are their concerns? Never assume they are the same as yours.

Please rest assured that ceding archaeological authority in this manner is not the same as encouraging a free for all, where anyone can dig, and anyone can say what they like about the past. Inclusive practice relies upon your hard-won skills and knowledge because listening is not the same as being silent. We have dual ethical obligations to people and communities in the present, and to people in the past. If you think about it, the long dead never ask us to tell their stories, yet we do it anyway, often with no reflection. Think on it. And ask yourself why you want to dig up someone else’s life? What are you motivated by? Why should any of us do this work? And, finally, ask how can we get our interpretations as accurate as possible in honour of the dead? I like to call it empirical honesty- always being true to the evidence as we engage in meaningful conversations in the present.

I am so glad that you aspire to be an archaeologist. Find your own answers to the ‘why’ questions. Once you do that, I can assure you that not only will you contribute meaningfully to society, but you will be enriched by the people you choose to work with and by the people you encounter only as traces in the ground. No promises on the Land Rover, though.

My best, Audrey

.