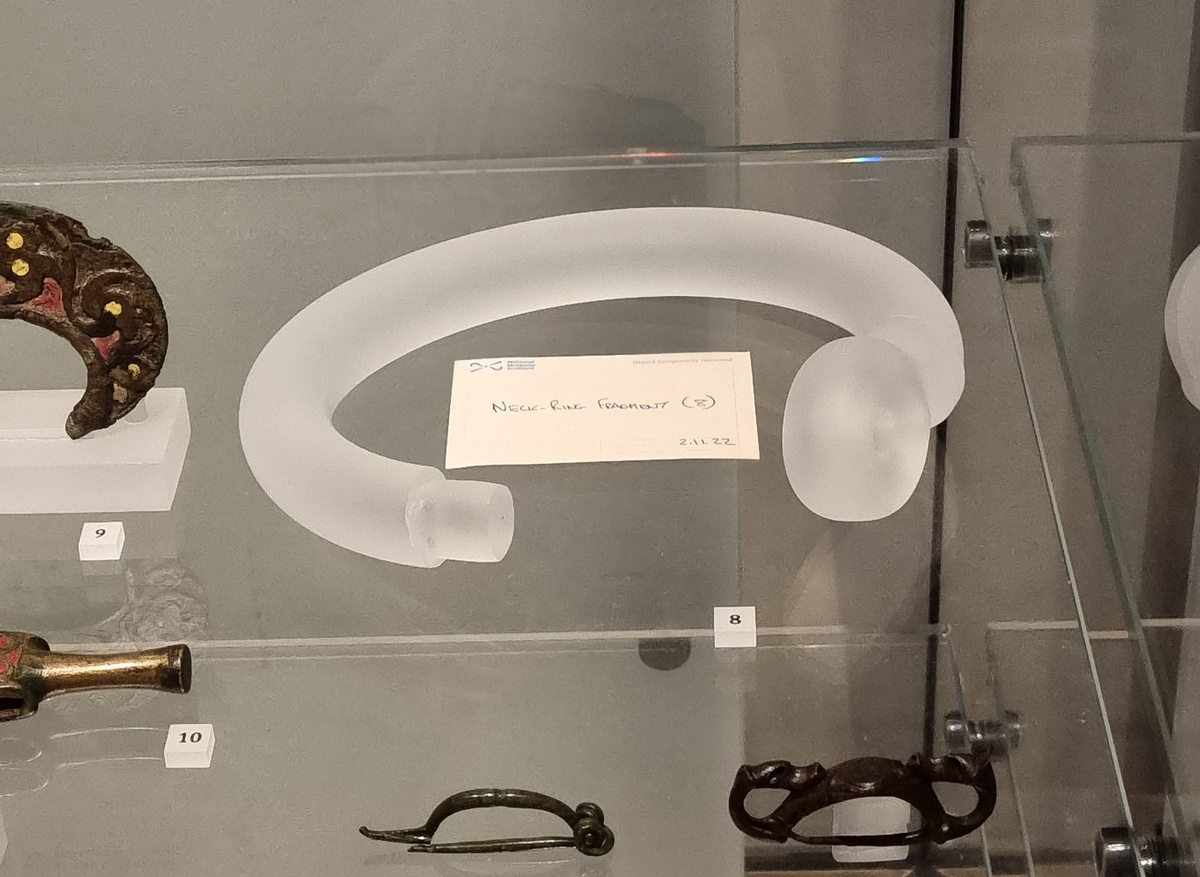

Do you ever visit a museum and see that an object seems to have vanished from its case? Have you ever wondered where it has gone?

Well, if it isn’t off display for an exhibition (museums often loan artefacts to other museums, or for special exhibitions) it is likely that it’s off display for research and - if it’s an Iron Age gold torc that’s missing - it’s possible that myself and Roland Williamson will be responsible for its case disappearance!

Over the last eight years, Roland and I have travelled the UK looking at torcs for our research. We have seen most: from the Netherurd terminal in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, to the Newark torc held at the National Civil War Centre in Newark, Nottinghamshire to the myriad torcs in the British Museum in London: we have had most off display to examine them.

But why is this important? Why aren’t photographs enough?

To be honest, we can understand a lot from photos, and we have enough of them: around 13,000 at last count from websites, catalogues, our own photos taken of objects in cases, etc, but when it comes to really understanding an artefact, you need to see it up close.

We look at Iron Age gold torcs from a craft perspective - how they were made, what tools were used, what the stages in the making of the torc were – and to decipher this you need to be able examine the object in detail. By getting the light just right, you can often see evidence of construction not easily visible and you can also see inside something (as any of you who follow our research will know, the clues to making can often be found on the back of an artefact, or on the inside….the places that were never meant to be seen). You can get a feel for the piece: it’s weight, how the decoration works in shifting light. All aspects that we are sure the Iron Age goldsmiths intended someone to appreciate.

So when an artefact vanishes from a case where does it go? Well, obviously, these pieces are precious, delicate and valuable. Moving a gold torc is no easy thing and it is not done on a whim: we have to apply to have an object removed for study and justify why in particular we need to see it. In the case of the Netherurd and Blair Drummond torcs in the photos above, although we had seen Netherurd a couple of times before, we were keen to look at it under a new microscope at NMS, and we also had a question about some damage to the back of the terminal (that was the subject of our Day in Archaeology blog last year). In the case of the Blair Drummond torcs we had not seen these before and so wanted to examine their methods of manufacture.

The pieces are taken off display and arrive in the research room in packaging which is in itself an artform: a careful and skilfully applied cradle of foam and pins, which keeps the torcs still and safe during their move. Museums are not just full of curators and researchers: the staff who are responsible for the mounting of museum artefacts, their conservation, their packing and transport are a hugely skilled and essential part of the team.

After careful unpacking, the torcs are laid out on foam mats to examine and we wear nitrile gloves (like surgeons would wear!) so we don’t damage the 2400 year old surfaces. Torcs are usually pretty robust and so can be handled (gold is a very strong material and, even if the sheet gold is only c.0.1mm thick like some of the tubular torcs, it still feels about as rigid as a fizzy drinks can). The Netherurd terminal is made from 0.7mm thick sheet gold and so feels quite solid in your hand. However, if an object is quite fragile (the Snettisham Great torc, for example, is not quite as solid as it appears, and the terminal joints are rather shaky!) then it may not be possible to move it much, with any moving/turning needed being carried out by a curator or museum artefact specialist.

We do not do these things lightly and, even after eight years, it is a privilege we do not take for granted: there is still a very special feeling you get when you see the empty case and realize that the item has been taken off display for you!

For us, the day at NMS was a success: under the microscope, we could clearly see the damage caused to the terminal (it seems that a tool slipped during decoration and the mark made was patched from the interior) and in the case of the Blair Drummond torcs we were able to confirm Fraser Hunter’s ideas of how the torcs were put together.

At the end of the day the torcs were repackaged and taken safely back to their case. Do go and see the torcs at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh and, if you’d like to know more about them, have a look at our website, The Big Book of Torcs.

I really hope the torcs enjoyed their trip out of the case!