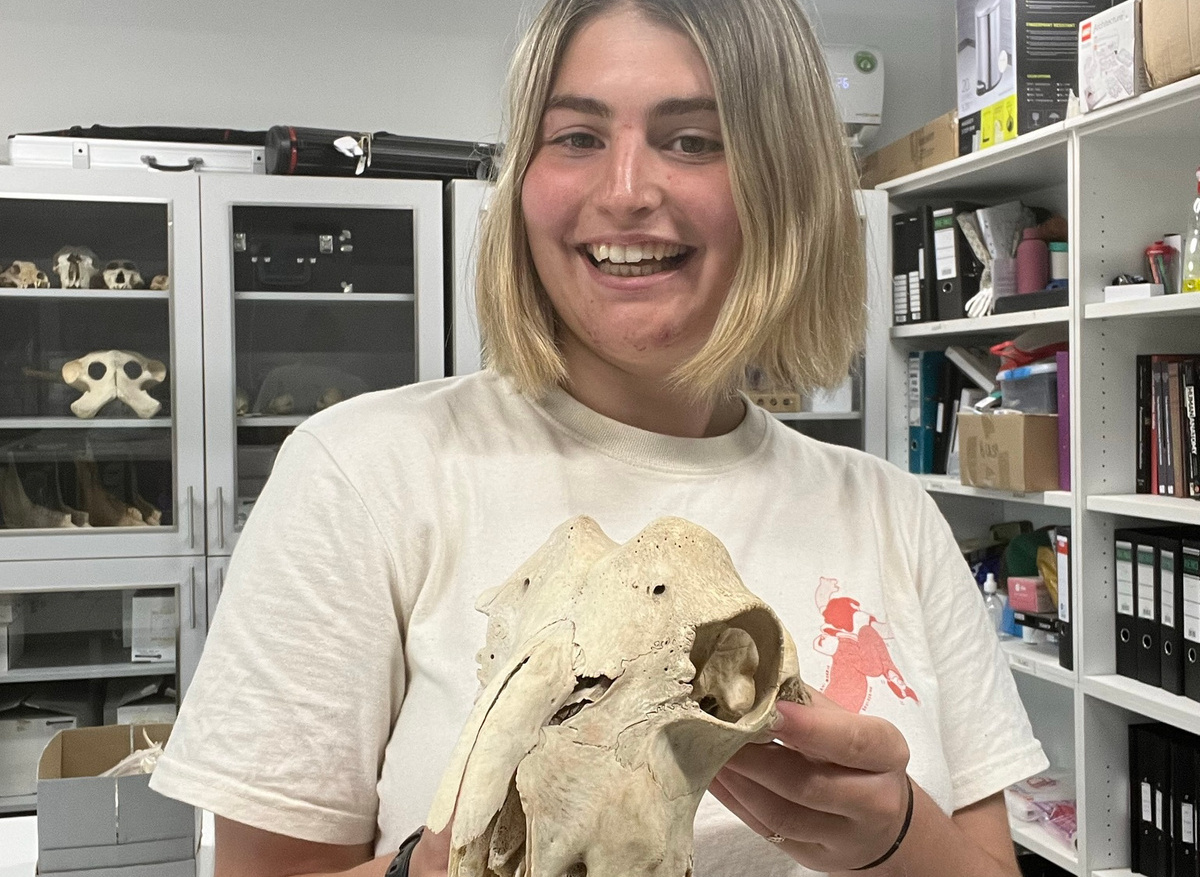

It’s hot. Really hot. So hot that my 10 minute walk to the lab leaves me sweaty and feeling dehydrated. But that’s a small price to pay for doing a zooarchaeology internship in Cyprus. It’s awesome! I’m spending two months working at the Cyprus Institute, in their Science and Technology in Archaeology and Culture Research Centre (STARC). The main purpose of this internship is make 3D models of as many faunal specimens as possible using a technique called photogrammetry. The models can then be used for outreach, remote research, and as a digital record for the collection. My supervisor, Angelos Hadjikoumis, is trying to establish zooarchaeology as a field in Cyprus, and part of that involves developing a reference collection of different species to use as comparative specimens to help identify bones that are excavated during digs. There’s a huge amount of unseen work that goes into processing, recording, and curating a collection, and it’s been fascinating to see a more logistical side to the field. It’s also been really interesting to handle some more unusual bones - so far my favourites have been the griffon vulture, now a rare species in Cyprus, and dolphin skeletons.

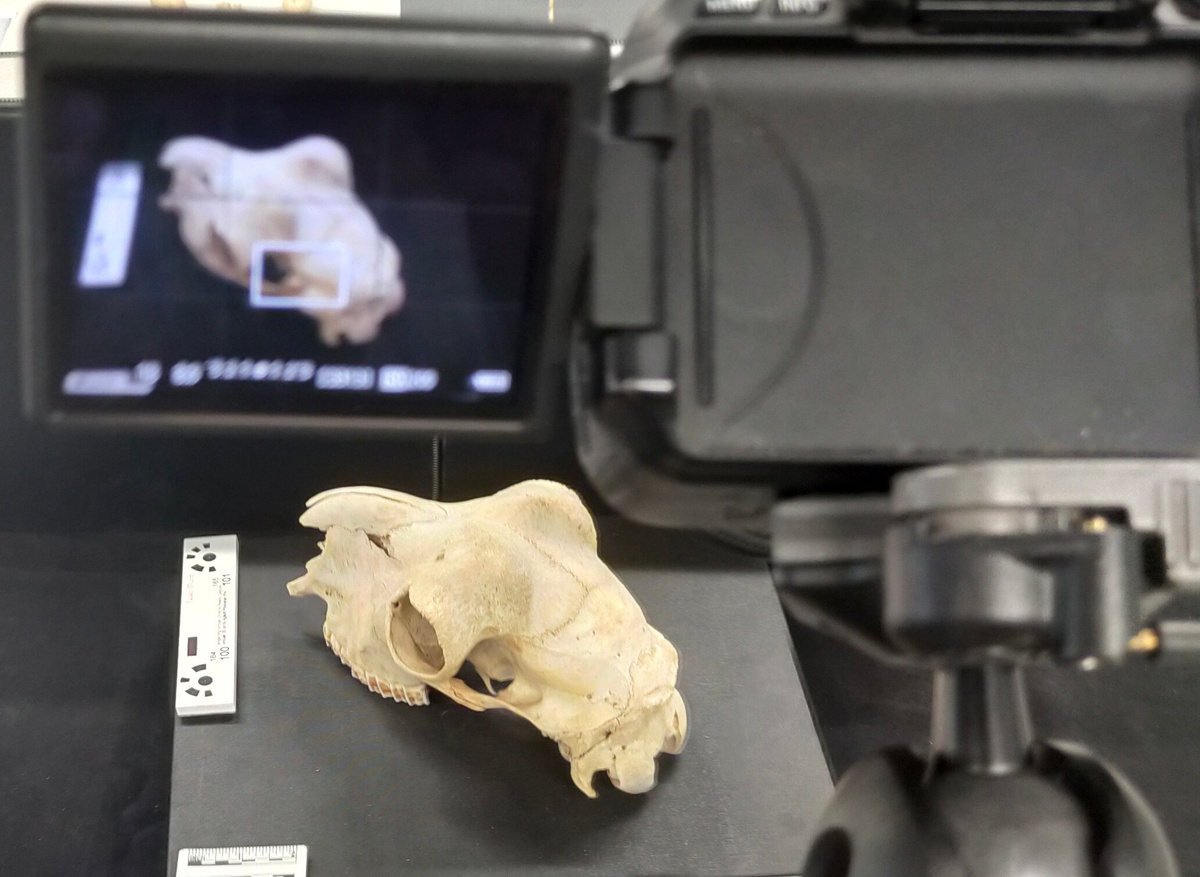

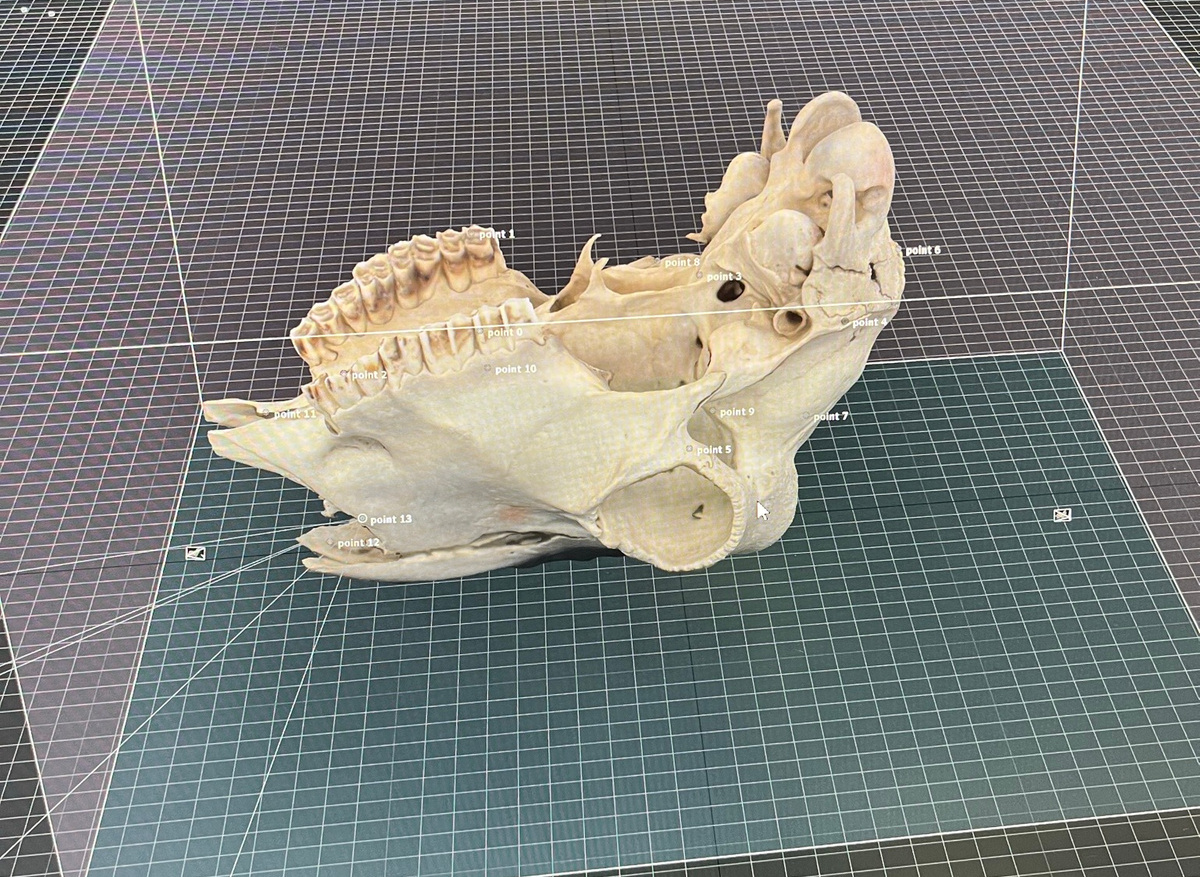

My day-to-day activities usually involve taking high-quality photographs that are used to make the 3D models. For architecture or smaller artefacts that have more detail, you can make a good model with 70-250 photos. For bones however, the smooth surface and lack of contrasting colours or details means that the modelling software can struggle to combine the pictures. For an average long bone, I take between 300-700 photos from a variety of angles so there’s more overlap between any two photos. I then convert them from RAW files to TIFF files, which are high-resolution images and don’t have as much ‘digital noise’ as a JPEG. The TIFF files are then ready to be imported into the modelling software (we use RealityCapture), where I can then make a 3D model. These last steps have to be done on the Cyprus Institute’s supercomputer in order to process the images, and can take several hours to make a model. For comparison, my laptop took 15hrs to get 20% of the way through a model, so you really do need good processing power!

If you’d have told me two years ago I’d be sorting bones in Cyprus, I probably would’ve laughed. My undergraduate degree at the University of Exeter was in Liberal Arts. I actually majored in English, having realised too late that my interests lay elsewhere. Luckily, Liberal Arts allowed me to take 50% of modules outside my major. I tried lots of different subjects and developed a research specialism in human-animal interactions, and in the final term of final year took a zooarchaeology module.

It. Blew. My. Mind!

Finally I’d found a subject that combined multiple disciplines and methods, one that taught me coding and lab skills. After the module ended I was left desperate for more, and was lucky enough to secure an internship with Exeter’s Centre for Human-Animal-Environment Bioarchaeology to work on a project about goat introductions into the UK over the summer. Although I had planned to start my Masters that September, I couldn’t choose between my two offers and was very burnt-out and stressed about how to afford them. I also realised that I’d fallen in love with zooarchaeology and wanted more experience in the field in case I ended up changing disciplines. I deferred my Masters offers, applied to funding schemes, and spent a year ‘living archaeologically’; reading as much as I could and staying on at Exeter as a research assistant, helping in the lab and talking to people about their experiences whilst working a part-time retail job. The highlight of the year was winning a scholarship to an excavation in Colorado to analyse their faunal remains. It was definitely a trial by fire but I learnt a lot!

Ultimately, I was lucky enough to secure an ESRC 1+3 studentship for UCL’s Science and Technology Studies (STS) department to fund my Masters and PhD, focusing on human-animal interactions in rewilded landscapes. I’ve also been able to keep studying zooarchaeology alongside STS; I think working across disciplines always improves work and encourages you to think differently about a topic. For me, zooarchaeology offers a really useful deep-time element that provides a different perspective on how the relationship between humans and animals has evolved. I also firmly believe that archaeologists are some of the nicest people out there; everyone I’ve met is so enthusiastic about their work, and supportive of my forays into the field. So if you ever meet a zooarchaeologist in the wild, don’t be shy, we really do just want to talk to you about morphological differences between goat and sheep bones!