Excavations of the Roman legionary barrack blocks at Caerleon (the Roman ISCA) during the late 1920’s produced large quantities of broken Roman Pottery. Amongst the sherds preserved at the National Roman Legion Museum, Caerleon, are many so-called ‘tazze’ fragments. Sometimes also called 'thuribulum’, these pedestalled vessels often preserve traces of burning from their use as incense offering cups for Roman religious ceremonies and prayer. They could also have separate covers which allowed the incense to rise through arched apertures in their matching, frilled, spire-like chimneys. The commonplace use of a white slip to coat the tazze, and their thumb-impressed frilled or hatched decoration, probably helped to set them apart from other, more worldly, pottery, as ritual objects.

But the quantity of tazze from Caerleon, and the low number of candlesticks, oil lamps (Caerleon, in Britain, is a long way from warmer oil-producing areas) and open lamps recovered, raised the question as to whether tazze may have been also utilized for lighting, as open lamps, within the fortress?

Recalling the old forensics adage that ‘it is difficult for someone to enter or leave the scene of a crime without either leaving something behind or taking something with them’ (Locard’s Principle) Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales curator, Mark Lewis, contacted Lucy Cramp, one of Britain’s leading experts in the forensic study of archeological organic residues, at Bristol University, to investigate whether it might be possible that some residues of the Roman organics burned in the tazze might still be preserved, encapsulated within their porous fabrics.

This was a big ask of the pottery, for burial conditions in Caerleon are commonly not kind to the pottery recovered. Any Roman organic residues may have decayed away or dissolved or washed away over time. A further worry was that the pottery may have become contaminated with organic material since excavation, through handling, or in storage in cardboard boxes, or from dust.

There was only one way to try to find out…

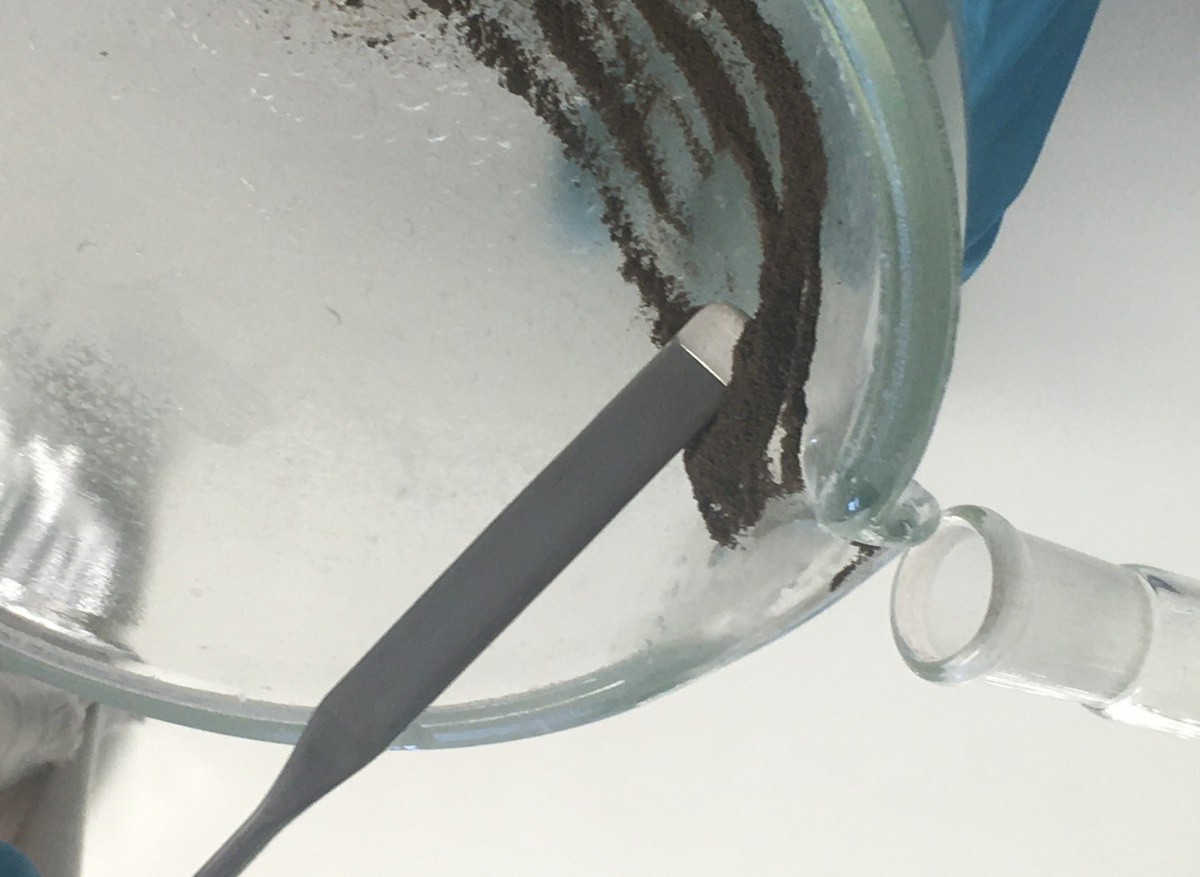

A selection of tazza sherds, some with visible traces of burning like the examples shown here, were selected from the 1920s Caerleon Prysg Field Barracks and Defences excavations. These were photographed before they were delivered to Lucy at the laboratory in Bristol University for partial destructive sampling for analysis.

To prepare the sherds for analysis, the surfaces of small portions of the sherd were cleaned using a modelling drill and then a small piece (about the size of a £1 coin) chipped off with a chisel. This fragment was then crushed in a mortar and pestle and extracted using organic solvents. This extracted out any lipid molecules trapped in the matrix of the ceramic fabric. These mixtures of compounds can then be separated out using gas chromatography (GC), and each peak identified by combining GC with mass spectrometry. This gives us a ‘finger-print’ that can be related back to the signatures of possible resources that people may have used in the past.

Very little lipid was actually recovered from these sherds, which may mean that fats from any original products had nearly entirely degraded away, or that the vessels did not contain fatty or oily products in the first place. However, traces of animal fats were recovered from two of the sherds, along with markers that form during the heating of animal fats. It might be that these tazze were used for burning of a kind of tallow, or that the animal fat was used as a ‘base’ to which other substances, such as perfumes or resins were added, for which evidence has not survived.

Contact details

Lucy Cramp and Mark Lewis

University of Bristol and National Roman Legion Museum, Caerleon